Home

HOW DERONJIC DIVIDED THE JUDGES

Dissenting and separate opinions of judges Schomburg and Mumba on potential effects of the punishment imposed on Miroslav Deronjic.

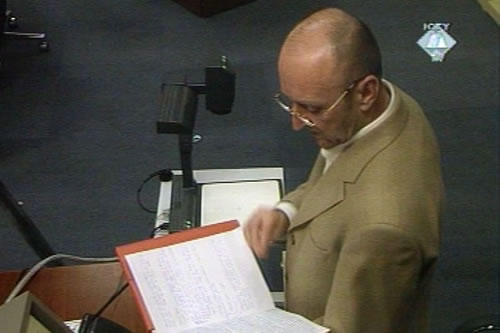

Miroslav Deronjic

Miroslav Deronjic Judges deciding by majority is not a rare occurrence at the International Tribunal. In the very first judgment, delivered in the Dusko Tadic case, the judges were divided on their judgment about the character of the conflict. Consequently, the accused was acquitted by majority (2:1) on all counts charging him with grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. Last year General Stanislav Galic was sentenced by the majority of the bench to 20 years in prison for the shelling and a campaign of terror in Sarajevo. Judge Nieto-Navia remained in the minority – he felt that ten years would have been adequate punishment.

The opposite happened yesterday in the Miroslav Deronjic case: judges Florence Mumba and Carmel Agius opted for the punishment of ten years in prison and outvoted Judge Schomburg who was in favor of a punishment twice as severe.

In the statement of reasons for his dissenting opinion, the German judge states that the prosecution limited the criminal prosecution and the evidence presented against him to one incident in the context of a larger criminal plan. Schomburg thinks that there unquestionably was a plan to ethnically cleanse the "entire municipality of Bratunac, and not only the village of Glogova." In the opinion of the German judge, "these crimes are of a far more serious nature than those committed in Glogova" on 9 May 1992, when at least 64 civilians were killed, large part of the village was razed to the ground and the entire Muslim population of the village was expelled. Deronjic, as the president of the local SDS board and the Bratunac Crisis Staff, was the highest ranking political figure in the municipality.

Having studied all the statements given by the accused and the transcripts of his testimony at other trials held before the Tribunal, Judge Schomburg points out that “it remains extremely questionable” why Deronjic was not indicted as a co-perpetrator in a joint criminal enterprise leading to the Srebrenica massacre in 1995. In his view, it transpires on a prima facie basis that there should be enough reason to indict him for his participation in the massacre, "based only on his own confession". In July 1995, Deronjic was Karadzic's "civil commissioner" for Srebrenica; at the time of the deportations and mass executions, he was the highest ranking representative of the civilian authorities in the region.

The German judge thinks that Deronjic's guilty plea warrants only little weight as a mitigating factor in the sentencing. The evidentiary value of his statements and testimony at other trials, Schomburg deems, would remain “extremely limited, until the Accused is prepared to clarify which details are true and which are not.” Reminding that at one of the trials Deronjic admitted that some of his statements were “partially untrue”, the German judge concludes that such an “unsound mixture of truth and lies” cannot be accepted as a basis for a lighter sentence. Schomburg also expresses his doubts as to the sincerity of Deronjic's remorse and points to the fact that after his guilty plea he tried to play down his responsibility from one testimony to another.

In the conclusion of his dissenting opinion, Judge Schomburg states that any sentence less than 20 years in prison “could be seen an incentive for politicians, who might in future find themselves in a similar situation as Deronjic was as of December 1991, to act in the same manner.” They would know, the Judge says, that even if they are brought before criminal court they will be able to buy themselves “more or less free by admitting some guilt and giving some information” to the prosecutor.

Judge Schomburg dissent has led Judge Florence Mumba of Zambia to attach to the judgment her own separate opinion in which she explains why she was in favor of a lighter sentence for Deronjic. International justice, Judge Mumba states, “is not about unfair retribution; if that were the case, humanity should forget about reconciliation and peace”. This Tribunal, in her view, “is not about vengeance, using pen as the firearm, much as the victims’ plight has been acknowledged.” According to her, that would lead to an acceptance of “the erroneous view that you can conquer hatred with hatred.” A harsh sentence for an accused person who has pleaded guilty could, Judge Mumba deems, be construed as vengeance. It is her belief, however, that a guilty pleas is “a first step to rehabilitation of the offender and a positive factor towards reconciliation of the offended community.”