Home

ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN

In addition to four ‘official’ legal advisers, paid by the Tribunal’s Registry, Radovan Karadzic has some thirty ‘unofficial’ advisers and assistants from law schools all over the world, from Holland to New Zealand and Australia. They all do research and draft the innumerable motions the accused has been heaping over the Trial Chamber on a daily basis. They do it pro bono

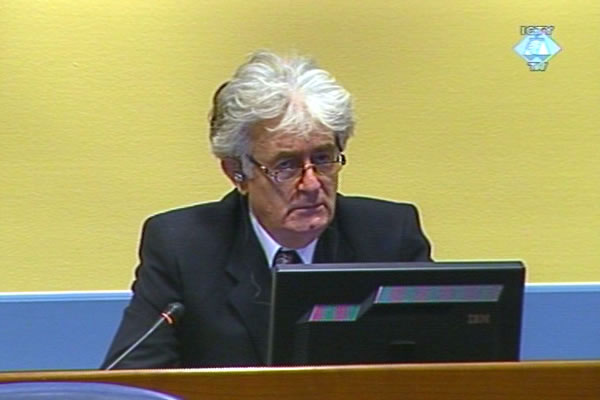

Radovan Karadzic in the courtroom

Radovan Karadzic in the courtroom Radovan Karadzic has gathered an impressive number of legal advisers that he could have used well in Pale, when he was a president. Had they been there to advise him then, Karadzic probably would not now find himself in the present predicament.

Slobodan Milosevic gathered around him big shot lawyers with big personal political agendas: American Ramsey Clark, Canadian Christopher Black or Frenchman Jacques Verges, although it would be more accurate to say they gathered around Milosevic. Karadzic’s legal team, on the contrary, consists of professors, assistant lecturers and graduate students from law schools from about a dozen countries: from Holland, Italy, Greece and Switzerland to the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. They all specialize in international criminal law.

Among them are Goran Sluiter and Elies van Sliedregt, professors at the Amsterdam University, former senior legal adviser at the Tribunal Dr. Alexander Zahar from the Australian Griffith Law School, Professor Speedy Rice of the Washington and Lee University in the USA. In the final footnote of his motions, Karadzic expresses his gratitude to the professors who have helped him draft the motions or students who have done legal research.

Karadzic now has four ‘official’ legal advisers and one investigator approved by the Tribunal’s Registry: Peter Robinson, Goran Petronijevic, Mladen Magdelinic, Marko Sladojevic and Milivoje Ivanisevic. All of them are on the Registry list and payroll. Karadzic is not pleased with the pay grade determined by the Registry: they have classified them as ‘support staff’. According to the Registry, legal advisers are there to assist the lead counsel: in this case, that is the accused himself.

The remaining thirty-odd professors, assistant lecturers and postgraduate students are ‘unofficial’ advisers who, as Peter Robinson says, help Karadzic pro bono. When he was asked if they were maybe paid from the sum of 36 million German Marks (about € 18 million) taken by Karadzic in the spring of 1997 from the National Bank in Banja Luka, Robinson replied he knew nothing about that. In Fugitives, a documentary film, Republika Srpska prime minister Miroslav Dodik alleged that Karadzic took this money. According to Robinson, the main if not the only motive of Karadzic’s ‘unofficial’ advisers is to implement in practice what they deal with in theory at their universities and contribute in that way to the development of jurisprudence before international criminal courts.

So far, they have not been particularly successful: most of Karadzic’s motions have been dismissed. Some of them were labeled ‘frivolous’, ‘vexatious’ and described as ‘a waste of time’, not only for those who drafted them but for the prosecution that has had to reply to them and the Trial Chamber that has had to rule on them.

They deserve an ‘A’ for effort, though. Karadzic has set an absolute record among the accused in the number of motions, requests, letters, replies and other correspondence between him and the Trial Chamber and the Registry. During the ten months of his detention, Karadzic has signed and filed a total of some 360 various documents: more than one a day. The Trial Chamber with Judge Bonomy presiding is trying to rule on Karadzic’s motions and requests as soon as possible to clear up the ground for the trial to start; yet the judges have found it hard to keep up with the pace set by Karadzic’s ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ legal advisers filing documents on a daily basis.

In the background of Karadzic’s ‘war of motions’ there is hope that the Tribunal might close before the end or even before the start of his trial, with a little help of his Russian friends. Right now, that hope may not be as ‘frivolous’ and ‘vexatious’ as some of Karadzic’s motions. According to the UN Security Council resolutions in force, the mandate of the permanent and ad litem ICTY judges runs out on 31 December 2009.

Linked Reports

- Case : Karadzic

- 2009-05-26 HOLBROOK’S ‘DIPLOMATIC SLEIGHT-OF-HAND’

- 2009-05-25 KARADZIC’S MOTION ON THE ‘HOLBROOK AGREEMENT’

- 2009-05-08 KARADZIC PAYS THE PRICE FOR HIS CHOICE

- 2009-06-03 KARADZIC WONDERS WHY HE HAS BEEN INDICTED DESPITE SO MUCH EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE

- 2009-06-11 LORD OWEN ‘RELUCTANT’ TO TESTIFY FOR THE PROSECUTION

- 2009-07-08 KARADZIC’S MOTION ON HOLBROOKE AGREEMENT DENIED