Home

BOSNIA AND THE DESTRUCTION OF IDENTITY

'The brutality of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina shocked a generation and was a conflict whose far-reaching impact continues to influence policy-makers today. The enormous devastation was to become a seminal marker in the discourse on cultural heritage and prompted an urgent reassessment of how cultural property could be protected in times of conflict' said Helen Walasek at the Conference 'The Destruction Of Cultural Heritage, Post-War Reconstruction And Trust Building' held in Pula

Helen Walasek

Helen Walasek The massive intentional destruction of cultural and religious property during the 1992–1995 Bosnian War is recognised as the greatest destruction of cultural heritage in Europe since World War Two. The destruction, which took place almost entirely during violent campaigns of ethnic cleansing, was one of the defining and most widely reported features of the conflict – and one of the most condemned. The brutality of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina shocked a generation and was a conflict whose far-reaching impact continues to influence policy-makers today. The enormous devastation was to become a seminal marker in the discourse on cultural heritage and prompted an urgent reassessment of how cultural property could be protected in times of conflict.

Ethnic cleansing and the destruction of heritage

The aggressive ethnic cleansing of the Bosnian War, waged against civilians by secessionist forces in their attempts to create ethnically homogenous territories, aimed not only at removing the living unwanted ‘Other’, but at systematically removing the material traces of their historic presence from the landscape. Far from being simply an unfortunate side-effect of the conflict, the destruction of cultural and religious property was one of its central objectives. Perpetrators left no doubt of the reasons for the destruction, openly voicing their intentions of obliterating the built evidence of the expelled communities’ roots in a locality in the hopes of discouraging those who survived from ever returning.

While analysts today rarely consider the Bosnian War to be a religious or ethnic conflict, nevertheless, those driving the war certainly mobilised the past and vigorously promoted negative perceptions of ethnonational and ethnoreligious differences. A forceful exclusivist ideology drove the extensive, systematic, and intentional destruction of cultural and religious property during the war as symbols of both ethnoreligious and a historically diverse Bosnian identity. That destruction was unmistakably identified by victims, perpetrators and observers alike as being an intrinsic part of ethnic cleansing.

Bosnia became the paradigm of the intentional destruction of cultural property during conflict, not only among heritage professionals, but across disciplines from the military to the humanitarian aid professions in the years following the end of the war as they struggled to find answers to the questions raised by the inability of the international community to prevent the horrors of ethnic cleansing with its accompanying destruction of cultural and religious property.

Identifying the perpetrators

However, this was not the equivalent mutual destruction of cultural and religious property by the three principal warring parties in the conflict. This has not been borne out by the evidence or expert assessments and investigations, such as those of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). These have shown convincingly that the greatest part of the deliberate destruction of religious and cultural property took place during campaigns of ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, the principal perpetrators of such campaigns were found to be Bosnian Serb forces and their allies, who then controlled 70% of the territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina (and universally identified themselves by religion as Serbian Orthodox), followed by Bosnian Croat separatists (whose ethnoreligious identity was Roman Catholic). Although Bosnian government forces (labelled by many commentators as ‘Muslim’) were found to have breached the Geneva Conventions, it had no policies of ethnic cleansing and did not carry out such operations.

The removal of structures from the landscape that marked the long historic presence of the ethnoreligious groups targeted for removal in pursuit of creating a visibly mono-ethnic space, then, should not be seen as a separate phenomenon, but recognised as being an integral part of ethnic cleansing and all the acts associated with that process, including forced expulsion, imprisonment in concentration camps, torture, mass murder and mass rape.

Intentional and systematic

The majority of attacks on cultural and religious property during the Bosnian War, then, had clearly identifiable characteristics: they were intentional and systematic; the destruction was the result of deliberate targeting (frequently by detonating explosives inside structures) rather than collateral damage during military action; attacks took place in the context of the mass expulsions of specific communities; and, most destruction occurred far from the frontlines, or where fighting had ceased and areas were in secure control of the perpetrators.

One of the most notorious episodes was the systematic demolition of the domed sixteenth-century Ferhadija Mosque and eleven other historic mosques and important Ottoman monuments in Banja Luka, de facto capital of secessionist Bosnian Serbs. The destruction took place in 1993, more than a year after the war began, in a city which never saw any military action. These were steps towards the creation of a mono-ethnic realm with a fictitious past, where that same year the mayor of Bosnian Serb-held ethnically-cleansed Zvornik could declare to journalists of the once Muslim-majority town: ‘There were never any mosques in Zvornik’.

Destruction of an identity

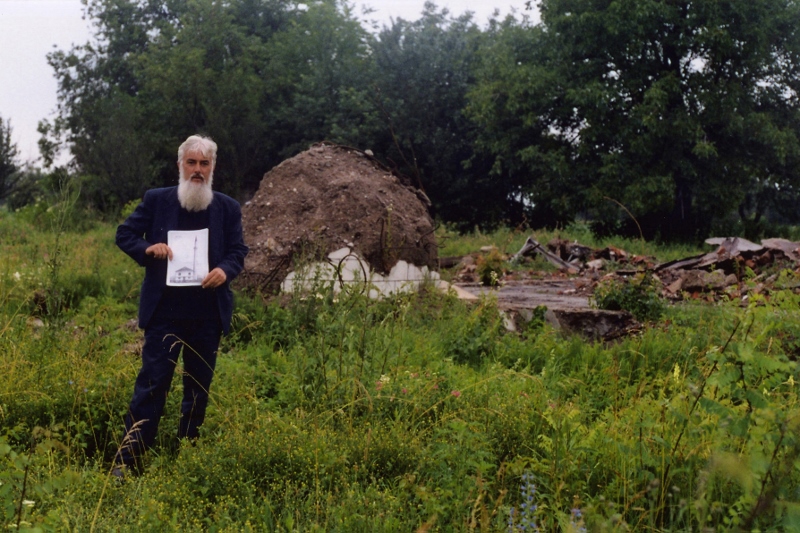

Statements by perpetrators unambiguously show their understanding of the effects of the destruction on group identity. Milan Tupajić, wartime chief of the Bosnian Serb-held municipality of Sokolac, spelled this out when he testified at the ICTY in The Hague, describing how over a few days in September 1992 all the mosques in the area were demolished. Asked by ICTY prosecutors why he thought the mosques had been destroyed, Tupajić explained: ‘There’s a belief among the Serbs that if there are no mosques, there are no Muslims and by destroying the mosques, the Muslims will lose a motive to return to their villages.’

However, in cities like Sarajevo and Mostar, not so easily overrun, structures with no ethnonational affiliation, but which embodied Bosnia’s centuries-long cultural diversity were targeted, such as museums, archives, libraries and institutions like Sarajevo’s Oriental Institute. For this was not only the violent eradication of particular ethnoreligious identities, but an attempt to deny the existence of a collective Bosnian identity. The two iconic episodes in international perceptions of the destruction of cultural heritage in Bosnia-Herzegovina were the burning of the National Library (Vijećnica or former Town Hall) in Sarajevo in August 1992 after its bombardment with incendiary shells by the Bosnian Serb artillery ringing the city, and the intensive shelling of Mostar’s sixteenth-century Ottoman Old Bridge (Stari Most) by Bosnian Croat forces (HVO), leading to its collapse in November 1993.

Yet while these attacks in urban settings aroused global condemnation, it was in towns and villages across wide swathes of ethnically-cleansed countryside where the destruction was worst, largely out of sight of the international media. The types of built heritage destroyed or badly damaged were overwhelmingly religious, and overwhelmingly Ottoman, or associated with Muslims. By the end of the war, with one exception, not a single intact minaret was left standing in areas controlled by Bosnian Serb forces.

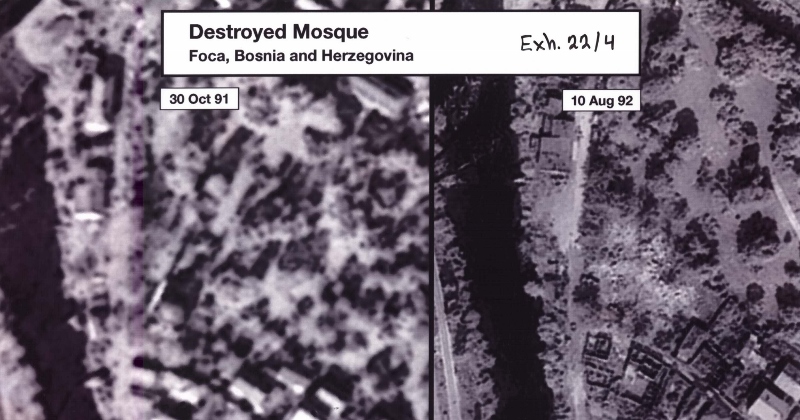

Some of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s most important historic monuments, such as the sixteenth-century Aladža Mosque in Foča, were razed to the ground and their sites levelled by Bosnian Serb forces. Meanwhile, in Stolac, secessionist Bosnian Croat forces and their supporters totally destroyed or left in ruins all the town’s mosques and its Orthodox church, along with other Ottoman-era structures.

Significantly fewer Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches and monasteries were assaulted than Muslim or Ottoman sacral structures. Nevertheless historic buildings like the neo-Baroque Orthodox Cathedral in Mostar and the sixteenth-century Orthodox monastery at Žitomislić were dynamited into rubble, while at Plehan, the Franciscan Monastery was repeatedly shelled by Bosnian Serb forces, before being destroyed by a truck bomb carrying two tons of explosives.

Car parks and garbage

In rural settings or the outskirts of towns, ruins of attacked structures were frequently left to crumble. But in town and village centres there was often active intervention: ruins were bulldozed, remains trucked away and sites levelled so not a single trace could be seen above ground level. The cleared and levelled sites of what had once been religious buildings went on to be used for parking cars and communal rubbish bins, and as spaces for holding markets or chopping wood. A few were built on, but most remained as inexplicable blank spaces at the heart of otherwise densely-built environments.

Where did the remains of these destroyed structures go? They were crushed, dumped and buried, thrown in rivers and lakes or municipal landfill sites, often far from their original location. The rubble from destroyed mosques has even been found covering the bodies of Muslims massacred during ethnic cleansing and buried in mass graves, as at Brčko.

International responses to the destruction

But what actions did the international community take to confront and address this intentional and systematic destruction of cultural and religious property during the conflict? As the destruction continued, the ineffectiveness of international legal instruments for protecting cultural heritage in times of conflict such as The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict of 1954 was all too evident. The Ferhadija Mosque and the Stari Most were not destroyed until 1993, a year and more after the war had begun. Yet the international community seemed unable to prevent such acts happening, despite the presence of UNPROFOR peacekeeping troops and humanitarian aid organisations like UNHCR and ICRC across the country, along with a string of United Nations Resolutions condemning ethnic cleansing.

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) was to be the sole international organisation to take any form of early action, sending consultant experts to assess the destruction and publishing their findings in ten Information Reports on war damage to the cultural heritage in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. They hoped these reports would inform the international community of the scale of the destruction, encourage efforts to stop it and promote active intervention to protect the heritage in what the first report called ‘a cultural catastrophe in the heart of Europe.’

From the start the PACE reports raised what remains an aspiration even today: the importance of integrating support for the cultural heritage into traditional humanitarian aid and the importance of emergency assistance before the conflict ended. The Council of Europe parliamentarians in 1993 urged international actors to beware of hiding behind ‘false reasons’ for not intervening at an early stage, nor to feel ashamed of being concerned for the cultural heritage while people were suffering, pointing out the socio-economic and psychological dimensions of the destruction.

Yet, while international humanitarian law clearly mandates protection of a people’s cultural property, being seen to be privileging buildings over people was problematic for most international organisations, even those concerned entirely with heritage protection. Support for preserving historic monuments or for museums and other heritage organisations, if considered at all, was regarded as of little importance in the face of what were considered more pressing humanitarian problems – and this is still the case. Combined with an unwillingness to provide emergency assistance to protect the built heritage while the conflict was ongoing (usually on the grounds that it might be attacked again) there was almost no assistance to protect Bosnia-Herzegovina’s cultural heritage during the war.

Heritage and human rights: the ICTY and implementing Dayton

The search for justice for victims of the 1992–1995 Bosnian War was to become an important testing ground of international humanitarian and human rights law, including the protection and preservation of cultural and religious property, the right to a people’s enjoyment of their cultural heritage and the development of concepts of the link between cultural heritage and group identity. The ground-breaking legal precedents of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) have played a seminal role in this respect, although there were other significant decisions from, for instance, the International Court of Justice and the Human Rights Chamber for Bosnia & Herzegovina.

The inclusion of crimes relating to cultural and religious property in the ICTY Statute was an important addition to international legal instruments. Yet the Tribunal’s most distinctive contribution to the prosecution of crimes against cultural heritage has been its landmark indictments and judgements which, in case after case, have established that the deliberate destruction of structures symbolised a group’s identity were a manifestation of persecution and a crime against humanity.

The Dayton Peace Agreementthat ended the war in 1995 focused above all on reversing the effects of ethnic cleansing in an attempt to restore Bosnia-Herzegovina’s prewar diversity. Uniquely, it recognised the role that cultural heritage destruction had played during the conflict and among the treaty’s eleven annexes, Annex 8 mandated the creation of a Commission to Preserve National Monuments. Restoration and preservation of Bosnia’s destroyed and damaged historic monuments should – in theory – have taken place within the framework of the Dayton Agreement, supporting the return of refugees and displaced people to the homes and communities from which they had been forcibly expelled.

Yet, with a few exceptions, the international community’s involvement in heritage restoration in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the post-conflict years can be characterised by a narrow focus on a small number of high-profile projects, chief among them the World Bank-led UNESCO-coordinated restoration of Mostar and the Stari Most. The iconic bridge came to be extensively mobilised as a visible symbol of the ideas of reconciliation and the reconstruction of relations between Bosnia’s ethnonational groups the international community was keen to promote in the aftermath of the war, with the result that a substantial amount of the international funding available for post-conflict heritage restoration was swallowed up by the many projects in Mostar.

Meanwhile, elsewhere, refugees and the displaced returning to the places from which they had been ethnically cleansed, focused literally on ‘restoring’ their communities – including the right to equality in the public space through the reconstruction of the built markers of their community identity, often in the face of determined obstruction and violence from hardline nationalist local authorities and their supporters, many of whom had been active participants in ethnic cleansing.

Yet there was virtually no linkage of heritage restoration to the return process by international actors, and little discussion of justice or human rights in their discourse on heritage rebuilding. International support for restoration projects for war-damaged or destroyed historic structures in Republika Srpska or locations in the Federation where there was vocal opposition from hostile ethnonational power structures was non-existent as donors feared to become involved in what they perceived as difficult and contentious settings.

It was to take almost a decade after Dayton for restoration of cultural heritage to be seen as an important part of the post-conflict recovery process, by which time the huge amounts of international funding that had once been available for reconstruction had moved elsewhere.

---------------------------

About the author: Helen Walasek is the author of Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (Ashgate 2015). Walasek was Deputy Director of Bosnia-Herzegovina Heritage Rescue (BHHR) for which she worked 1994–1998 and an Associate of the Bosnian Institute, London 1998–2007. She made many working visits to Bosnia during and after the 1992-1995 war, including as an Expert Consultant for the Council of Europe.

The Conference was organized as a joint project of five civil society organizations from Croatia, B-H, Serbia and the Netherlands, with the financial support of the EU's Remembrance - Europe for citizens - programme

Photos

Linked Reports

- Case : Miscellaneous

- 2017-09-21 INTERACTIVE NARRATIVE “ICTY: THE KOSOVO CASE” PRESENTED TO THE PUBLIC

- 2017-06-23 TARGETING MONUMENTS: EXHIBITION OPENS IN SARAJEVO

- 2017-06-07 BRAMMERTZ SOUNDS ALARM ABOUT WESTERN BALKANS DEVELOPMENTS

- 2018-01-27 SENSE IN MOSTAR AND AHMIĆI

- 2018-04-04 EXHIBITION „TARGETING MONUMENTS“ OPENS IN THE HAGUE

- 2018-04-04 JUDGE AGIUS REMARKS AT THE OPENING OF EXHIBITION