Home

‘NEIGHBORLY AGREEMENT’ ON POPULATION EXCHANGE

In his evidence at the trial of Ratko Mladic, the former president of the Novo Sarajevo Executive Board claimed that non-Serbs were not persecuted and discriminated against in his municipality. Muslims and Croats regularly received pensions, humanitarian and medical aid. Despite that, the non-Serbs were ‘timid’, but the witness did not specify why. The court heard about the exchange of population in November 1992

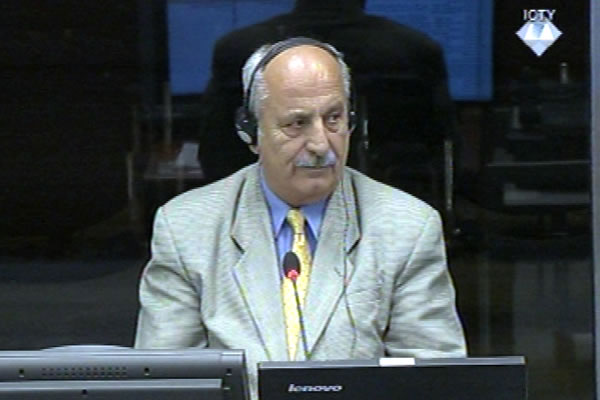

Branko Radan, defence witness at Rako Mladic trial

Branko Radan, defence witness at Rako Mladic trial In his evidence in Ratko Mladic’s defense, Branko Radan, former president of the Executive Board in Novo Sarajevo denied the allegations that non-Serbs were persecuted and discriminated against in his municipality. In his statement to Mladic’s defense the witness said that at the beginning of the war the Serb authorities in Novo Sarajevo decided not to discriminate against anyone in any way, and in particular not to torture or abuse the non-Serb inhabitants. ‘On the contrary, safety was guaranteed to everyone’, the witness said.

According to the witness, about 2,000 Muslims and around 300 or 400 Croats remained in the Serb part of Novo Sarajevo. They regularly received their pensions, humanitarian aid and had access to health care. Some ‘individuals’ did illegally obtain property, but some of them were made to return it after the municipal authorities intervened. When the judges asked who those ‘individuals’ were, Radan said those were mostly Serbs who had acquired the property that belonged to ‘others’ unlawfully. Muslims and Croats were ‘timid’, the witness noted.

Radan did admit that a group of criminals was active in Grbavica. The nine men that were led by Veselin Vlahovic Batko ‘caused problems’ not only to Muslims and Croats, but also to Serbs. The civilian and military police stepped in at one point, and the group was dealt with. The witness’s claim that the troublesome group ‘was active over a period of just two or three years’ caught Judge Orie’s attention. The presiding judge asked the witness to clarify when exactly the group left the municipality for good.

This question was asked several times, and Radan kept saying that Batko ‘first’ left in late 1992, only to return later. Radan wasn’t able to specify when Batko and others ‘left for good’ or indeed, if they ever did.

The judges also insisted that the witness explain a paragraph from the statement where he said that in the second half of 1992 ‘there was an exchange: Serbs left Sarajevo in 15 to 20 buses at Vrbanja Bridge’. Contrary to what he said in his statement, in court Radan argued that this was not an exchange. As he explained, the departure of Serbs from Sarajevo on 15 November 1992 was the response of the other side to the Serbs’ ‘act of good will’ of 30 September 1992, when Muslims left from Grbavica and went to Sarajevo. It was a ‘neighborly agreement’ between Serbs and Muslims living near the frontline. This ‘had nothing to do with the authorities’.

In the examination-in-chief Radan claimed that Serbs, unlike Muslims and Croats, hadn’t been preparing for the war. In the first part of her cross-examination, prosecutor Camille Bibles confronted the witness with the prosecution’s evidence to the contrary. According to one of the documents she showed Radan, in 1991 the JNA was training and arming SDS members. By 11 May 1992, 69,000 Serbs were armed, Ratko Mladic wrote in his war diary.

The prosecution will continue cross-examining Branko Radan tomorrow.